When you bite into an apple or crunch on a celery stick, you’re eating something remarkable that your body cannot digest. Yes, that’s right. Dietary fiber—the structural component that gives plants their firmness—passes through your digestive system mostly unchanged. Yet, this indigestible material is absolutely crucial for your health.

What exactly is fiber, and why can’t we digest it?

Dietary fiber consists of complex carbohydrates found in plant cell walls. Unlike starches and sugars, fiber is made up of molecules linked by bonds that human digestive enzymes cannot break. We simply don’t have the necessary enzymes to dismantle these plant structures—a limitation seen in most mammals.

This “limitation” is actually an evolutionary advantage. Our inability to digest fiber sets the stage for a remarkable partnership with trillions of microorganisms living in our intestines.

The two types of fiber: soluble and insoluble

Fiber comes in two main forms, each serving unique roles in your gut:

- Soluble fiber dissolves in water to form a gel-like substance. Found in foods like oats, beans, and fruits, it slows digestion and helps control blood sugar levels. Think of it as nature’s slow-release mechanism.

- Insoluble fiber does not dissolve but absorbs water as it moves through the digestive system. Rich in whole grains and vegetables, it adds bulk to stool and helps food move more quickly through your stomach and intestines.

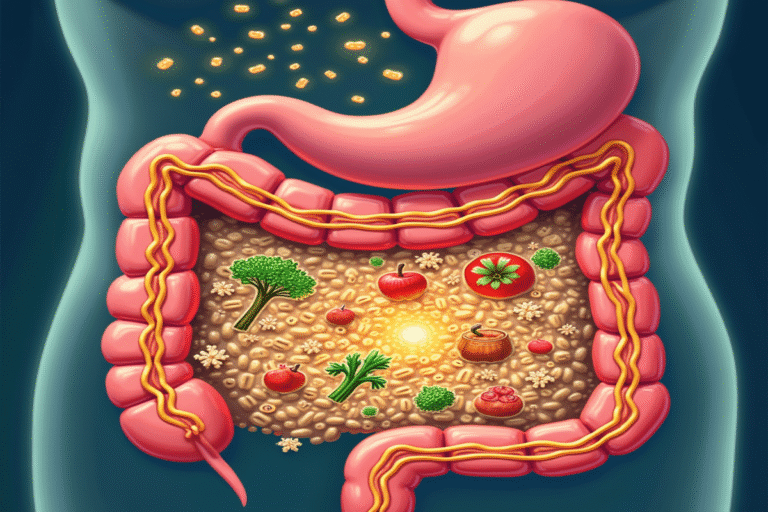

Your gut: A fermentation chamber billions of years in the making

Here’s where things get interesting. While you can’t digest fiber, the estimated 100 trillion bacteria in your gut thrive on it. Your large intestine acts as a fermentation chamber—a place where microbes break down fiber in processes similar to making beer, sourdough bread, or kombucha.

This fermentation produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate, propionate, and acetate. These are not just waste products—they’re crucial signaling molecules that influence almost every system in your body. For example, butyrate is the main energy source for the cells lining your colon and helps regulate genes related to inflammation and cancer prevention.

Your microbiome: As unique as your fingerprint

Your collection of gut bacteria is as unique as your fingerprint. Factors like your genetics, how you were born, your history of antibiotic use, and your diet shape your personal mix of microbes, which in turn controls how effectively fiber is processed in your body.

This explains why two people can eat the same high-fiber meal but have different digestive experiences. Your own microbial community determines which fibers are broken down and what beneficial compounds are produced.

Beyond digestion: Fiber’s wide-reaching benefits

The benefits of fiber go far beyond regular bowel movements. Studies have linked fiber intake to:

- Reduced inflammation throughout the body

- Stronger immune function

- Lower risk of heart disease and stroke

- Better weight management and metabolic health

- Improved mood and brain function

- Lower risk of certain cancers, especially colorectal cancer

One remarkable discovery is that SCFAs produced from fiber fermentation can influence brain function through the gut-brain axis. These molecules seem to help regulate neurotransmitter production and neuroinflammation, potentially affecting anything from stress response to cognitive ability.

The evolutionary mismatch: Our modern fiber crisis

Our ancient ancestors probably ate between 100-150 grams of fiber daily from a variety of plants. Today, the average American eats barely 15 grams per day—a major shortfall that leaves our gut microbes “starved.”

This sudden dietary shift has happened too quickly for our bodies to adapt. Our digestive systems are still tuned for the fiber-rich diet our ancestors ate over millions of years. Without enough fiber, our microbiome becomes less diverse and produces fewer beneficial compounds, setting off a chain of health problems.

The fiber adjustment: Time and patience matter

It takes time for the benefits of increased fiber intake to show. Research suggests it can take 2-4 weeks for your gut microbiome to adapt to new fiber-rich foods. When you increase fiber suddenly, you may experience digestive discomfort as your microbes expand to handle the new “feast.”

This adjustment period is why many people feel bloated or uncomfortable when they suddenly eat more fiber. Your gut needs time to grow the specific bacteria that digest different types of fiber.

Fiber diversity: The powerful missing link

The latest research shows that fiber diversity is as important as fiber quantity. Different fibers feed different helpful bacteria. By eating a variety of fiber sources—from resistant starch in cooled potatoes to beta-glucans in mushrooms to pectin in apples—you build a healthier and more resilient gut microbiome.

Scientists have found over 100 unique fiber structures in plants, each with its own fermentation pattern and preferred bacteria. This means our current “soluble vs. insoluble” fiber categories are just the beginning of understanding fiber complexity.

The future of fiber science

Scientists are now exploring personalized fiber recommendations based on your unique microbiome. The idea of “precision prebiotics”—customized fiber supplements made to support specific helpful bacteria—is the new frontier in gut health.

Researchers are also studying how compounds produced from fiber could be used to treat diseases like inflammatory bowel disease, metabolic disorders, and neurological conditions.

The plant material our own bodies can’t digest has become one of the most exciting areas in nutrition science. Fiber is not just a digestive aid—it’s the key link between what we eat and the trillions of microbes that help control our health. By feeding our microbial partners, we nourish ourselves, forming one of nature’s most fascinating and important partnerships.