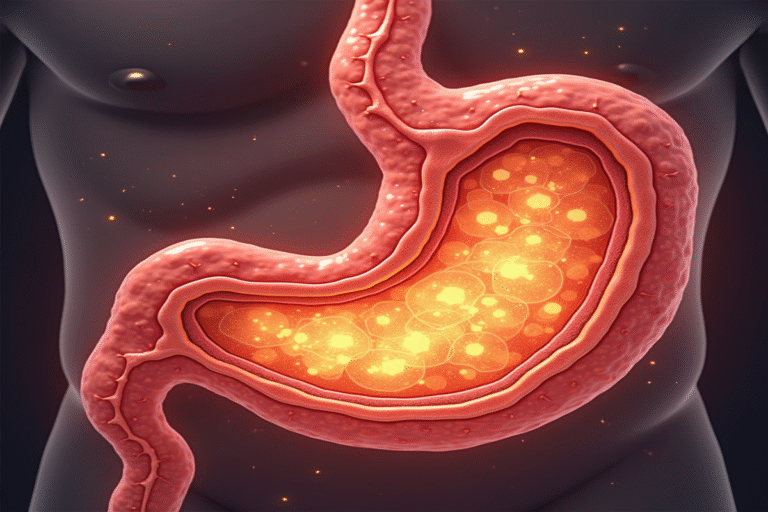

Have you ever wondered how your stomach can contain acid strong enough to dissolve metal, yet somehow doesn’t digest itself? It’s one of the most remarkable examples of evolutionary problem-solving happening inside your body right now.

The Remarkable Power of Stomach Acid

Your stomach produces hydrochloric acid with a pH between 1.5 and 3.5 — acidic enough to dissolve zinc and corrode many metals. If this acid touched your skin, it could cause serious chemical burns. Yet somehow, this powerful corrosive substance safely exists inside your body, working tirelessly to break down your meals.

Gastric acid serves several important functions:

- Breaks down proteins into smaller peptides

- Activates digestive enzymes like pepsin

- Kills harmful bacteria and pathogens in food

- Helps absorb nutrients like calcium and iron

The Acid Factory: How Your Stomach Produces This Powerful Substance

The inner lining of your stomach (the gastric epithelium) contains specialized cells called parietal cells. These acid-producing cells use an enzyme called H+/K+ ATPase — also known as the proton pump — to push hydrochloric acid into the stomach cavity.

When you eat, smell, or even think about food, your body signals these cells to pump hydrogen ions (H+) into your stomach, creating a highly acidic environment. This process uses a lot of energy — your stomach cells can use up to 400 calories per day just to produce acid!

The Protective Shield: Why Your Stomach Doesn’t Digest Itself

Your stomach uses several clever defense mechanisms to protect itself:

1. The Mucus Barrier

The stomach’s first line of defense is a thick layer of mucus secreted by surface epithelial cells. This mucus acts as a physical barrier between the stomach lining and the harsh acid. The mucus contains bicarbonate ions that neutralize acid, creating a pH gradient — right at the stomach wall, the pH is nearly neutral, even though the acid is highly concentrated just millimeters away.

2. Rapid Cell Renewal

Your stomach lining completely replaces itself every 3–7 days. This rapid turnover means damaged cells are quickly shed and replaced with new ones before serious injury can occur. Few other tissues in the body renew themselves this quickly.

3. Tight Cell Junctions

The epithelial cells lining your stomach are connected by tight junctions, forming a nearly impermeable seal that prevents acid from seeping between cells and damaging deeper tissue layers. These “cellular zippers” are strengthened by specialized proteins that maintain their integrity.

4. Prostaglandins

These locally acting, hormone-like substances increase mucus production, boost bicarbonate secretion, improve blood flow to the stomach lining, and help maintain the tight junctions between cells. When certain medications (like aspirin or other NSAIDs) block prostaglandin production, stomach ulcers can result.

When Protection Fails: Understanding Stomach Problems

This delicate balance can be disturbed. Helicobacter pylori bacteria can burrow through the mucus layer and damage the stomach lining. Regular use of NSAIDs (like ibuprofen) suppresses protective prostaglandins. Excessive alcohol, smoking, and stress can also weaken these defenses. When protection fails, problems like gastritis and peptic ulcers can develop.

The Evolutionary Dance

This balancing act between potent acid and sophisticated protection represents millions of years of evolutionary refinement. Animals that eat more meat tend to have more acidic stomachs to kill pathogens and break down protein, while plant-eaters often have less acidic stomachs.

Your stomach’s ability to contain this powerful acid while protecting itself is a testament to the complexity of human physiology. It’s an elegant answer to a challenging problem — how to use a corrosive substance for digestion without harming the body itself.

Next time your stomach growls, remember the amazing cellular machines hard at work to create acid strong enough to dissolve metal, while simultaneously guarding your body from that same acid — all without you ever noticing this microscopic marvel.